The Man Who Changed California Seraphina Wang

G. Edward White is a Professor of Law at the University

of Virginia School of Law and was a

former law clerk to Earl Warren. He wrote Earl Warren: A Public Life to reveal

write about the man behind Earl Warren. Besides Earl Warren: A Public Life, he

has written several other books, including the two prominent books, The

American Judicial Tradition and Tort Law In America.

On July 9,

1974,

Earl Warren, died of cardiac arrest with his wife, Nina, and his daughter,

Honeybear, next to him. Surprisingly, after his death, Warren ceased to be "a figure

of widespread public interest."1 However, during his lifetime, Warren was hailed as one of America's greatest chief justices.

In Earl Warren: A Public Life, written by G. Edward White, White sought

to discern what made Warren one of the best chief

justices and what he did to change America.

Earl

Warren was born on March 19, 1891 and later attended the University of California, Berkeley. At Berkeley, Warren tended to see questions of

obedience "as one with moral dimensions."2 He discouraged

cheating, even if it was "cheating with dignity and pride."3

Warren showed an interest in political matters during

college, and sought out other careers related to law and justice. In one case

he later tried, the Point Lobos case in 1936, Warren prosecuted four of the five

defendants for the murder of Albert Murphy. The entire trial took eight weeks

ending in January of 1937 with Earl King, Earnest Ramsay, Frank Conner, and

George Wallace sentenced to prison terms ranging from five years to life. As a

governor, Warren was not a moderate but an activist trying to use office power

to further goals; he sought to retain progressivism in California and to

"support affirmative governmental action" on behalf of the disabled.4

In 1947, Warren supported a three cent increase in tax on gasoline to create

money for highway projects. He vetoed a bill in 1949 which stated that all University of California employees must sign an oath

declaring they are not associated in any way with communism. Instead, Warren signed the Levering Act

into effect in 1950 requiring all Californian employees to sign an agreement

that they did not associate with the Communist Party. Warren also "endorsed social

security" in California.5 Eventually, Warren was offered the

position of Supreme Court Justice. As a result, Warren finished his tenure as

governor and moved to Washington D.C. to start a new chapter in

his life as Chief Justice.

In

1953, Warren was appointed the Supreme Court Chief Justice. While Warren kept an interest in

administrative matters, Warren could not replace older

justices with new ones as he had done in California, meaning that the judges

often held differing opinions. One of his prominent cases was Brown v. Board

of Education. Warren's main concern was how to

"eradicate segregation in public schools" and how could it be

implemented effectively. 6 In December of 1953, Warren argued that the Court could

invalidate Plessy v. Ferguson if five justices would vote for the

invalidation. Also, Warren stated that the Fourteenth

Amendment justified that all citizens were given the rights of life, liberty,

and property. He successfully persuaded all of the other eight justices to

support a single opinion to end segregation. Another major trial during Warren's reign was the

investigation of John F. Kennedy's assassination. Warren, along with the Warren

Commission, ruled that Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald only and

no other gunman was involved with the shooting. However, many other committees,

such as the Select Committee rebuffed this result, convinced that there had to

be another gunman involved in the shooting. To Warren, Oswald was the perfect

man to kill the president since Oswald "had been a misfit all his

life" and was incapable of working with anyone.7 Warren relied

on the FBI and CIA to make a final judgment that Oswald did indeed act alone,

even though he initially refused to examine the FBI file on Oswald because he

feared that would affect national security.

Before

he became the Chief Justice, Warren believed that ethical

principles were necessary for enlightened government. Warren's concern for conduct

became characteristic for him as a California public official. He refused

to have a campaign organization because he thought it was too interested in

"maintaining their own patronage" and would not benefit the public.8 He also believed that the Bill of Rights

checked, not defined, individual freedoms, interpreting it as a pursuit of

justice. Warren considered education as a right, since it formed the

basis of civilization, believing that the Constitution didn't "envisage in

unrestricted right."9 By 1958 though, Warren showed signs of rethinking

his stance on reapportionment matters. He felt that the protection of rights

and responsibilities made in the Constitution should be represented through

officials. He believed that the judiciary should "reform the

malapportioned legislatures" because reapportionment potentially meant

equal participation for all citizens.10 Warren also believed that humans

were susceptible to bad influences that should be suppressed because they were

often destructive. Warren strongly disapproved

pornographic books and believed that teenage lust could be suppressed if teens

were taught why looking at these books was wrong. On court, Warren spoke against purveyors of

obscenity and denied pornographers the rights of the First Amendment. In 1972, Warren called for the restoration

of a moral tone in America. He declared that crime was

a social issue that could be reduced by the removal of environmental factors

that make it grow. He cultivated public outrage about corrupt law practices and

attempted to shame lobbyists. By using government as a moral role model, Warren felt he was helping his

people avoid temptations.

When

Nixon won the presidential election and became president in 1968, Warren faced a dilemma: either

stay as Chief Justice or resign. By the end of 1968, Warren chose to resign after Nixon

became president, and in June of 1969, Warren retired. Predicting that

Warren Burger was to be his replacement, Warren "disassociated himself

from the Burger Court" because he sensed that the Court now resided in the

enemy's hands, as Burger often disagreed with Warren's views.11

After his resignation, Warren kept chambers in the Court building and selected

law clerks. Warren regularly visited the West Coast for vacations and to

get away from the press. He combated the presence of special interests, growth

of political machines, and corruption in of government. Morality, progress, and

patriotism were three qualities Warren included in his ruling of

cases; he wanted citizens to also live according to the laws and stay loyal to America. Like other progressives, Warren encouraged active

government because he wanted the government to always be flexible in making

changes whenever necessary. He wished to make the government a way to represent

the people's opinions rather than rule authoritatively. G. Edward White's main thesis was that Earl Warren

wasn't just any ordinary California governor and Chief Justice.

He thought that Warren took every opportunity he

had and made it a chance "for him to grow and face a new challenge."12

From prison reforms to health insurance, it seems that White's thesis of Warren is true. For instance, Warren changed prison procedures

because he noticed that criminals who served jail time and gotten released

often times return to jail for a longer prison time. Warren believed that the

government needed to implement programs to instruct criminals how to avoid

crimes in the future. Through these programs, the criminals learn not to commit

the same crime again and to shun other crimes as well. Warren cared deeply for the poor;

he proposed state-supported health insurance for the destitute. As a

Republican, he considered himself to be a true representative of what the

Californians wanted and strove to change California's procedures in order to

fit the citizens needs. He constantly succeeded in having things his way by convincing

others why his viewpoint was correct. Through Warren's stubbornness, White

inferred that Warren changed what he wanted to change through persuasion.

White concluded that Warren indeed tried to seize every

opportunity in order to improve society through skill and experience.

G.

Edward White analyzed Earl Warren because he wanted to put in print some of Warren's good deed and to dispel

myths. Though Warren was often praised for his achievements during his

tenure as Chief Justice, White knew "there was much more to Earl Warren.¡¨13

White used different articles and interviewed people that knew Warren in order to write an

accurate book discussing Warren's achievements and his

family life. wanting to prove that he was a capable leader. Because people forgot

who Warren was after his death, Warren made sure to let people

always remember Warren and what he did to make California and the United States better. Originally, White

envisioned the book he wrote as an extended essay on Warren and his career. But when he

researched more about Warren, White came to the

conclusion that an extended essay would not do Warren any justice. Instead, White

chose to write a conventional biography in order to pen down and disucss Warren¡¦s accomplishments. White

specifically wanted to portray Warren as the progressive who

transcended the "political context of its origins" and as an educated

reformist.14 He believed Warren's vision of America as a powerful nation was a

vision that many people shared during his lifetime. Also, White juxtaposed Warren the public figure versus

Warren the private person to contrast his professional and personal life. White repeatedly wrote about common

themes and attitudes about Warren to show the consistency in Warren with regards to his

decision-making and problem-solving, such as morality and patriotism.

The

New York Times ¡§Book Review¡¨ hailed the Earl Warren: A Public Life

as a phenomenon. Because of Warren, the Warren Court acted "as a principal

national engine of reform" and remade race relations and enlarged freedom

of expression and press.15 Warren was an affable and hearty

figure who was single-minded but did not take criticism well. When he became

Chief Justice in October, 1953, Warren argued that the separate

but equal doctrine of racial segregation was invalid. With his single-minded

personality, Warren managed to convince others of his opinion and

invalidated the separate but equal doctrine. From the beginning in his public

life, Warren showed that he was a moralist who despised corruption

and organized crime. Book Review discovered that Warren's progressivism was an

ahead of its time; Warren was a progressive but he

moved to a more liberal sense of concern for people. One finishes the book with

a respect for Warren and what he did for America. He was neither an

intellectual nor a philosopher, but possessed qualities generally not found in

politicians. Konrad M. Hamilton

from University of Iowa stated that Warren was guilty of civil rights

violations before landing the position of Chief Justice. Warren denied defendants the

access of attorney during interrogation sessions and did not inform them of

their rights. Hamilton criticized Warren for acting paradoxically by

promoting equal rights but not carrying out what he says himself. In brief, Warren "engaged in [the]

criminal procedure practices" at the eventually condemned when he became

Chief Justice.16 Hamilton argued that some people might want to

attribute political self-interest as a cause for Warren's actions. Despite the

criticisms, Hamilton rated the book as

insightful and worth a read. The book allowed readers a different view of America through Warren's life.

In

general, one main thing that could be improved was the flow of the four main

sections the book contained. Often times, White jumps from one decade to

another and back, making the book hard to follow. Although White's book did

point out some flaws, it also emphasized the accomplishments. Warren was the first and last

major liberal Chief Justice. He promoted the "protection of the individual

against the state" and allowed minorities the freedom of choice.17 Since

he believed in equality, Warren supported due process of

law for all peoples. Morever, he accomplished a lot as Chief Justice and as California's governor, but also spent

quality time with his family, a peculiar action for a devoted and preoccupied

Chief Justice. However, Warren made sure he at least spent

dinnertime with his family and even disconnected the phone line so nobody could

interrupt. Warren emphasized his children's morals and values. He

banned his children from pornography, threatening to severely punish them. Warren assumed if he prevented his

children from evildoings, then they would be less tempted to commit crimes as

adults. Believing education to be the key for a nation to be well-grounded, Warren provided the best schooling

to his children to ensure that they would eventually be successful in life. He

was strict on his children's studies and held high standards for grades. His

concern about his family and his children's upbringing showed people that not

only did he care about America but he also worried about

his children and wife thus making the citizens believe that he was truly

devoted in caring for everyone.

When

Warren became Chief Justice, he battled Brown v. Board of

Education, a case that especially affected the South where lynchings and

mob riots still existed. When Warren declared Plessy v.

Ferguson and separate but equal schools unconstitutional, many were

outraged. Warren thought minorities deserved the same education as

Caucasians. Though he and eight other justices ruled for Brown and against the

education board, it would take another reevaluation and several more years

before the Supreme Court ordered every state to abolish segregated schools.

This case eventually sparked the civil rights movement in the 1960's and led to

other court cases that struck down forms of discrimination. One difference that

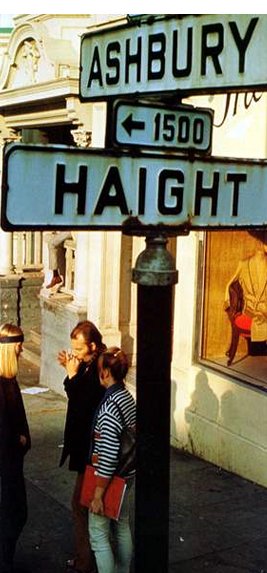

distinguished California from other states was the

Levering Act that Warren passed when he was

governor. Though other states had anticommunist oaths, the Levering Act proved

to be a controversial issue in California since many non-signers "felt

offended that they were accused of being Communists" if they did not sign.18

The non-signers thought they did not have to sign the oath in order to confirm

that they were anticommunists. Also, Warren improved prison conditions

by making sure the criminals understood their wrongdoings. State-funded health

insurance was also unique to California; now, everyone had the

possibility of receiving some kind of health care. Warren helped to change California through many ways.

White

viewed California as important by stressing

how a Californian governor stepped to the national level and became a Chief

Justice that forever altered America. Through his decisions, Warren brought justice and

terminated racism. Trying to be fair to all, Warren also encouraged citizens to

vote. White implies that Warren achieved so much as Chief

Justice primarily because he gained experience by engaging himself in politics

during his attendance at Berkeley and by becoming California's governor. Through his

experience, Warren learned how to become an effective leader and to

represent the people and their opinions. White believed California was a vital stepping stone

for Warren for preparing him for the national level of

leadership. Without California, Warren might never have been as

successful as he was. Warren needed California to expose himself to real

politics and reforms. White also inferred that California served as an example to

other states with its prison reforms, state-supported health insurance, and the

Levering Act to ensure the loyalty of the Californians. Most importantly, California helped shape Warren and his "identification

with the Republican party" along with his Progressive ideas.19

Indeed

Earl Warren was a different man from his media portrayal. With his prison

reforms and health insurance policies, California improved.

With his belief in equality, the nation improved. All in all, Warren brought

change that affected everyone in some way. He truly was one of California's best

governors and one of the most "significant figures in... American

history."20

1. White, G. Edward. Earl Warren: A Public Life. New

York: Oxford

University Press., 1982. 325.

2. White, G. Edward 15.

3. White, G. Edward 15.

4. White, G. Edward 102.

5. White, G. Edward 153.

6. White, G. Edward 163.

7. White, G. Edward 194.

8. White, G. Edward 221.

9. White, G. Edward 236.

10. White, G. Edward 239.

11. White, G. Edward 315.

12. White, G. Edward 9.

13. White, G. Edward 5.

14. White, G. Edward 6.

15. Lewis, Anthony. "Revolutionary Justice". The

New York Times Book Review 04 July 1982. 01 June 2008.

<http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res= 9D02E0D7123BF937A35754C0A964948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=4>.

16. Hamilton, Konrad M. "Untitled". Jstor. 01 June 2008

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/ 3377148.pdf>.

17. Lewis, Anthony.

18. White, G. Edward 117.

19. White, G. Edward 86.

20. White, G. Edward. 6